Introduction to algebra

Once you have an understanding of some key algebraic terms and techniques you can apply them to solve linear equations, as detailed in this page.

In brief, it covers the following:

- The definition of a linear equation

- How to rearrange a linear equation

- How to solve a linear equation in one variable

- How to write a linear equation in slope-intercept form

What is a linear equation?

Recall that an algebraic equation is just like an algebraic expression, but it also contains an equals (\(=\)) sign. For example, \(5 + d\) is an algebraic expression, while \(5 + d = 10\) is an algebraic equation. A particular kind of algebraic equation is a linear equation, or first degree equation:

A linear equation is an equation that only has variables raised to the first power, for example \(a\,–\,3 = 5\) as opposed to \(a^2\,–\,3 = 5\)

A linear equation with only one variable is called a linear equation in one variable, a linear equation with two variables is called a linear equation in two variables, and so on.

When we have a linear equation in one variable, we can determine the value of that variable and hence solve the equation by rearranging it so that the variable is by itself on one side of the equals sign. For example, to solve the equation \(c + 2 = 5\) you just need to get \(c\) by itself on one side of the equals sign.

Note that you can also solve linear equations in two or more variables, but this requires you to have the same number of equations as you do variables. Doing this is referred to as solving simultaneous equations, but this is not covered here (if you are interested in learning about how to do this, one example of a page you might find helpful is https://www.mathsisfun.com/algebra/systems-linear-equations.html).

Rearranging linear equations

Rearranging a linear equation in one variable in order to solve it requires you to ‘get rid of’ constants that are around the variable, that is, constants that have been added to it or that it has been multiplied by, for example. To do this, you need to undo whatever has been done with the constant by performing an ‘opposite’ operation. For example you might:

| Remove a constant that was… | By… |

|---|---|

| Added | Subtracting it |

| Subtracted | Adding it |

| Multiplied by | Dividing by it |

| Divided by | Multiplying by it |

The important thing to remember here is that whichever operation or operations you perform on one side of the equation, you must also do on the other side! This way you keep the equation in balance.

In other words, whatever you do to one side of an equation you need to do to the other side in the same step of working. For example:

| On the left hand side (LHS) of \(=\), if you… | On the right hand side (RHS) of \(=\), you must… |

|---|---|

| Add \(2\) (\(+2\)) | Add \(2\) (\(+2\)) |

| Subtract \(5\) (\(-5\)) | Subtract \(5\) (\(-5\)) |

| Multiply by \(7\) (\(\times 7\)) | Multiply by \(7\) (\(\times 7\)) |

| Divide by \(3\) (\(\div 3\)) | Divide by \(3\) (\(\div 3\)) |

Going back to the equation \(c + 2 = 5\), and to solve it you would undo the addition of \(2\) by subtracting \(2\) from both sides of the equation, as follows (note that with such a simple equation you don’t really need to use these techniques, but they will come in really handy with more complex equations - and it’s always best to start with a simple example!):

\[\begin{aligned} && c + 2 &= 5 \\\ \therefore && c + 2 - 2 &= 5 - 2 && \textrm{ (undo addition by subtracting) } \\\ \therefore && c &= 3 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!) } \end{aligned}\]Note that the \(\therefore\) sign shown above is just shorthand for ‘therefore’.

At this point, it is worth being aware of the fact that as you become more familiar with solving equations, you will find different ways of writing out your working that make sense to you. These may be slightly different to what is shown above, and that’s fine (as long as they are correct of course). For example, you may prefer to think of the ‘plus \(2\)’ as merely switching sides and becoming ‘subtract \(2\)’, as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} && c + 2 &= 5 \\\ \therefore && c &= 5 - 2 && \textrm{ (addition of }2\textrm{ on left becomes subtraction of }2\textrm{ on right)} &\\\ \therefore && c &= 3 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\]Steps for solving linear equations

Often multiple operations need to be undone in order to solve a linear equation in one variable. While this can require a bit of thought for complex equations, and as noted previously there are sometimes different techniques for solving the same equation, a general starting point is to follow these steps:

-

If your equation has brackets in it, expand these first (if you need a refresher on how to do this, refer to the Key terms and techniques page of this module).

-

If your equation has like terms in it, group these together next (adding or subtracting them from one side of the equation if required) and then simplify the equation (again, refer to the Key terms and techniques page of this module if required).

- If your equation requires more than one constant to be removed from the variable, undo one operation at a time in the following order:

- Remove anything that has been added to or subtracted from the variable

- Remove anything that the variable has been multiplied or divided by

- Check that the answer you have obtained is actually correct, by substituting the value back into the original equation and evaluating it. If it’s not correct, go back and see if you can find where you went wrong and work through the steps again.

Example: Solve the linear equation \(10d - 2 = 7(d + 1)\)

Solution: Following the steps above, we have:

\[\begin{aligned} && 10d - 2 &= 7(d + 1) \\\ \therefore && 10d - 2 &= 7d + 7 && \textrm{ (expand brackets)} \\\ \therefore && 10d - 2 - 7d &= 7d + 7 - 7d && \textrm{ (remove variable from RHS of equation by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && 3d - 2 &= 7 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 3d - 2 + 2 &= 7 + 2 && \textrm{ (undo subtraction by adding)} \\\ \therefore && 3d &= 9 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 3d/3 &= 9/3 && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && d &= 3 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\]Finally, substituting \(3\) back into the original equation gives \((10)(3) - 2 = 30 - 2 = 28\) on the left hand side, and \(7(3 + 1) = 7(4) = 28\) on the right hand side. So the solution is correct.

Once you have worked through the example above, have a go at solving some or all of the following linear equations:

\(\begin{aligned} && c + 3 &= 9 \\\ \therefore && c + 3 - 3 &= 9 - 3 && \textrm{ (undo addition by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && c &= 6 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && \frac{a}{3} &= 2 \\\ \therefore && 3(\frac{a}{3}) &= 3(2) && \textrm{ (undo division by multiplying)} \\\ \therefore && a &= 6 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && 3p + 2 &= 17 \\\ \therefore && 3p + 2 - 2 &= 17 - 2 && \textrm{ (undo addition by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && 3p &= 15 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{3p}{3} &= \frac{15}{3} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && p &= 5 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && 3y - 5 &= 13 \\\ \therefore && 3y - 5 + 5 &= 13 + 5 && \textrm{ (undo subtraction by adding)} \\\ \therefore && 3y &= 18 && \textrm{ (simplify)}& \\\ \therefore && \frac{3y}{3} &= \frac{18}{3} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && p &= 6 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && 3a + 4 &= a + 6 \\\ \therefore && 3a + 4 - a &= a + 6 - a && \textrm{ (remove variable from RHS by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && 2a + 4 &= 6 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 2a + 4 - 4 &= 6 - 4 && \textrm{ (undo addition by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && 2a &= 2 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{2a}{2} &= \frac{2}{2} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && a &= 1 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && 6n &= 20 + 2n \\\ \therefore && 6n - 2n &= 20 + 2n - 2n && \textrm{ (remove variable from RHS by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && 4n &= 20 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{4n}{4} &= \frac{20}{4} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && n &= 5 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && 5a - 5 + 10a &= -5 \\\ \therefore && 15a - 5 &= -5 && \textrm{ (simplify like terms)} \\\ \therefore && 15a - 5 + 5 &= -5 + 5 && \textrm{ (undo subtraction by adding)} \\\ \therefore && 15a &= 0 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{15a}{15} &= \frac{0}{15} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && a &= 0 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && 5(d - 2) &= 10 \\\ \therefore && 5d - 10 &= 10 && \textrm{ (expand brackets)} \\\ \therefore && 5d - 10 + 10 &= 10 + 10 && \textrm{ (undo subtraction by adding)} \\\ \therefore && 5d &= 20 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{5d}{5} &= \frac{20}{5} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && d &= 4 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && 3(d - 4) &= 12 \\\ \therefore && 3d - 12 &= 12 && \textrm{ (expand brackets)} \\\ \therefore && 3d - 12 + 12 &= 12 + 12 && \textrm{ (undo subtraction by adding)} \\\ \therefore && 3d &= 24 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{3d}{3} &= \frac{24}{3} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && d &= 8 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && \frac{2a - 1}{6} &= 4 \\\ \therefore && 2a - 1 &= 24 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 2a - 1 + 1 &= 24 + 1 && \textrm{ (undo subtraction by adding)} \\\ \therefore && 2a &= 25 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{2a}{2} &= \frac{25}{2} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && a &= 12.5 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && \frac{-2t + 1}{3} + 2 &= 6 \\\ \therefore && \frac{-2t + 1}{3} + 2 - 2 &= 6 - 2 && \textrm{ (undo addition by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{-2t + 1}{3} &= 4 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 3(\frac{-2t + 1}{3}) &= 3(4) && \textrm{ (undo division by multiplying)} \\\ \therefore && -2t + 1 &= 12 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && -2t + 1 - 1 &= 12 - 1 && \textrm{ (undo addition by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && -2t &= 11 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && \frac{-2t}{-2} &= \frac{11}{-2} && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && t &= -5.5 && \textrm{ (simplify - equation is solved!)} \end{aligned}\)

Slope-intercept form

When you plot a linear equation in two variables on a graph it forms a straight line. The most common way to write this kind of equation is in a format that clearly indicates two key properties of the line, and this is called slope-intercept form. It is as follows:

\[y = mx + c\]where:

- \(m\) is the gradient or slope of the line (for more on the gradient see the Derivatives page of the Introduction to calculus module)

- \(c\) is the y-intercept (the point where the line intercepts the y-axis, or vertical axis).

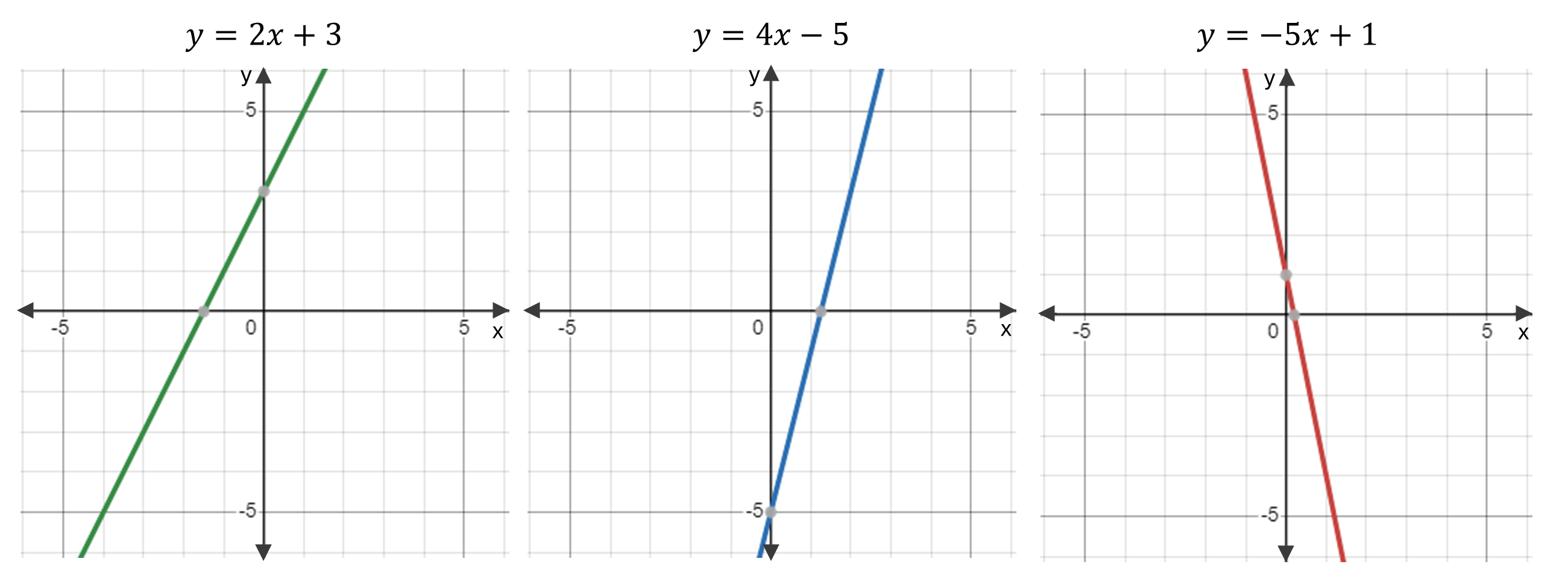

For example, the following linear equations are all in slope-intercept form:

\(y = 2x + 3\)

\(y = 4x - 5\)

\(y = -5x + 1\)

The graphs of these equations are as shown (note the different gradients and y-intercepts):

If a linear equation in two variables is not in slope-intercept form, it can be rearranged into this form by following the techniques described for solving linear equations.

Example: Rearrange the linear equation \(6x + 2y = 10\) to be in slope-intercept form.

Solution: Rearranging using the steps for solving linear equations gives:

\[\begin{aligned} && 6x + 2y &= 10 \\\ \therefore && 6x + 2y - 6x &= 10 - 6x && \textrm{ (remove } 6x \textrm{ from LHS of equation by subtracting)} \\\ \therefore && 2y &= 10 - 6x && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 2y/2 &= 10/2 - 6x/2 && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && y &= 5 - 3x && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && y &= - 3x + 5&& \textrm{ (rearrange)} \end{aligned}\]Once you have worked through the example above, have a go at some or all of these problems involving linear equations in slope-intercept form:

The gradient of this line is \(3\) and the y-intercept is \(-4\)

The gradient of this line is \(-0.4\) and the y-intercept is \(7\)

\(\begin{aligned} && -12x &= 6 - 3y \\\ \therefore && -12x + 3y &= 6 - 3y + 3y && \textrm{ (remove }-3y \textrm{ from RHS of equation by adding} \\\ \therefore && -12x + 3y &= 6 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && -12x + 3y + 12x &= 6 + 12x && \textrm{ (remove }-12x \textrm{ from LHS of equation by adding} \\\ \therefore && 3y &= 6 + 12x && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 3y/3 &= 6/3 + 12x/3 && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && y &= 4x + 2 && \textrm{ (simplify and rearrange)} \\\ \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned} && 4y + 20x + 8 &= 0 \\\ \therefore && 4y + 20x + 8 - 8 &= 0 - 8 && \textrm{ (remove } 8 \textrm{ from LHS of equation by subtracting} \\\ \therefore && 4y + 20x &= -8 && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 4y + 20x - 20x &= -8 - 20x && \textrm{ (remove } 20x \textrm{ from LHS of equation by subtracting} \\\ \therefore && 4y &= -8 - 20x && \textrm{ (simplify)} \\\ \therefore && 4y/4 &= -8/4 - 20x/4 && \textrm{ (undo multiplication by dividing)} \\\ \therefore && y &= -5x - 2 && \textrm{ (simplify and rearrange)} \\\ \end{aligned}\)