Gen-AI

Understanding Gen-AI

The easiest way to understand generative AI is to start at the beginning. This section introduces what it is and how it works. Understanding these ideas will give you a clearer picture of the technology behind the tools you might already be using.

A brief history of AI

The term “artificial intelligence” (AI) was first used in 1956 at a workshop held at Dartmouth College. This event is seen as the official start of the field of AI. But even before that, in the early 1950s, people were already interested in the idea of machines that could “think”.

These early machines were computers and other devices programmed to mimic human intelligence. One of the key figures in this area was Alan Turing. He suggested that if a machine could do tasks that usually needed human intelligence, then it could be said to “think”.

Despite the black-and-white broadcast and dated style, the 1961 CBS documentary The Thinking Machine, created for MIT’s 100th anniversary, still feels relevant today. Even more than sixty years ago, early computer technology—what would eventually lead to AI—sparked strong public reactions.

The documentary aimed to calm fears by showing that AI is simply computers following set rules, not something mysterious.

Jump to 31:13 in the video to see an example of early programming. In this clip, an MIT scientist demonstrates how a transistor computer called TX-0 created a movie script. The process may remind you of how we use Gen-AI tools today, giving you a point of comparison as you read on.

1960s and 1970s

Work on these “thinking machines” continued through the 1960s. Expert systems, programs designed to copy human decision-making using rule-based logic, became popular in the 1970s and peaked during the 1980s. They declined in the late 1980s during what is called the AI winter. These systems had two main parts: a knowledge base and an inference engine. They worked together to solve problems using if-then rules, similar to those used in TX-0. Today, AI technology more commonly uses systems like neural networks.

1980s and 1990s

From the late 1980s into the 1990s, digital technology advanced quickly. The internet appeared, and big data became important. Large collections of language data (called corpora) allowed breakthroughs in natural language processing (NLP)—the ability for computers to process, analyse and generate human language. This had been a dream for computer scientists since the 1950s. Public interest in AI grew again in 1997 when IBM’s supercomputer, DeepBlue, beat world chess champion Garry Kasparov.

2000s and 2010s

In the early 2000s and 2010s, computing power grew quickly thanks to more available data and better algorithms. With advancements in machine learning, and especially the rise of deep learning using a neural network called a transformer in 2017, computers got much better at processing language as humans naturally use it. In fact, the “T” in ChatGPT stands for this breakthrough technology.

What was so revolutionary about transformer technology in terms of NLP was its ability to go beyond linear processing. Older systems processed words one by one and struggled to remember words far apart from each other. Transformers process all words at once and give them attention weights, creating relationships between words based on their importance.

The first big success of this technology was in machine translation. Google Translate became much more fluent and accurate after using this new method. Transformer architecture changed NLP and, combined with techniques like reinforcement learning from human feedback, made tools like ChatGPT possible.

Today

On 30 November 2022, after several earlier versions, the company OpenAI released a demo of its AI chatbot called ChatGPT (version 4.0). ChatGPT amazed people with how well it could respond to written questions and instructions. Within just five days, over one million people were using it.

The technology behind ChatGPT is known as generative artificial intelligence (Gen-AI). This is different from older AI because it can create new content like text, images, or music, instead of just analysing or sorting existing data.

What is Gen-AI

AI

AI is a broad term that refers to computer systems designed to do tasks that usually require human intelligence, such as recognising speech, making decisions, or sorting large amounts of data. Traditional AI systems are trained to do one specific job really well. They follow patterns they have learned from data to give you consistent, reliable results. You use AI every day in things like:

- Search engines to find relevant results

- Recommendation systems like Netflix

- Fraud detection in banking

- Robotics for movement and interaction

While AI is highly accurate and efficient within its defined scope, it is limited to specific tasks and lacks the creativity and flexibility of newer technologies—making it important to understand where its strengths and limitations lie.

Gen-AI

Gen-AI is a newer type of AI that goes beyond pattern recognition to create original content. It learns from large datasets and uses that knowledge to generate text, images, music, or interactive environments. Gen-AI is more flexible and creative than traditional AI, with applications in:

- Writing blog posts, marketing copy, or academic summaries

- Generating realistic images for product design or advertising

- Composing original music tracks for videos or games

- Building immersive virtual worlds for gaming or training simulations

While Gen-AI’s versatility is exciting, it also raises concerns about job impact, misinformation, and misuse—making it important to understand both its benefits and risks.

Even Gen-AI is a broad term because the processes for generating different types of content are not the same. However, they share a common history and have similarities in how, for example, a chatbot produces text and an image generator makes a picture.

Models

To make sense of how Gen-AI tools work, it helps to understand the systems that power them. These systems are called models, and they’re at the heart of how tools like ChatGPT, DALL·E, and others generate text, images, and more. In this section, we’ll look at what models are and why they matter when using Gen-AI tools.

You may hear Gen-AI tools like ChatGPT called an LLM. This stands for large language model and is linked to natural language processing. An LLM is the system that allows a tool like ChatGPT to generate text. It is a computer system (a neural network) trained on lots of text that works inside software to create new text based on patterns it has learned.

Different companies behind Gen-AI tools have created their own LLMs. These models vary because their training data and processing are unique. This is important and will be discussed later.

You don’t have to be a big company to create an LLM, but it can be expensive. There are also small language models created by individuals or groups who share them freely on open-source websites. These can be used to create private GPTs.

Different again are generative image models, such as GAN or diffusion models. These are trained on pictures and text. They create new images based on patterns they have learned and the instructions they receive. These are the models behind tools like DALL·E 2, Stable Diffusion, or in the case of text-to-video generation, Sora from OpenAI.

Many tools today are multimodal, meaning their models are trained on multiple types of data in order to process and produce text, audio, images, videos, code and more. These tools still use the same technology of transformers that make LLMs possible, and are therefore sometimes referred to as large multimodal models (LMMs).

Most Gen-AI tools will also use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). This is a method that helps Gen-AI give better answers by using external material like documents specified by the user to inform its output. It first finds useful information within the external material, then uses that to create a response. Some tools can also fetch live data from the internet for local and timely answers.

In short, a model is a multidimensional mapping of identified patterns from large amounts of data, which can be text, audio, video or other types, and acts as a knowledge base for Gen-AI tools.

Training

Most LLMs are developed as pre-trained models. This means that as they were given raw data and used unsupervised learning to find patterns with no labels or correct answers. This ‘learning’ is done by applying a model’s mathematical frameworks (algorithms) to a sample dataset whose data points serve as the basis for the model’s future output. These overfitted models can generalise from the training data, but like a jack-of-all-trades, need tailoring to be able to do more specific tasks well.

This tailoring is called fine-tuning, which uses supervised and reinforcement learning. Both of these training types require input or oversight from humans. In supervised learning, humans label extra data for the model to process. In reinforcement learning, the model learns through trial and error and humans correct it with rewards or penalties. Think of it like cooking: pre-training teaches basic techniques, fine-tuning focuses on a cuisine, and reinforcement learning perfects a specific dish through practice.

Reinforcement learning has been pointed to as one cause for hallucinations because models might learn that any answer is better than no answer. This can lead to incorrect or invented information. For example, if you ask a tool to produce sources with citations, it will give an answer, but the sources may be fake.

Gen-AI outputs can be biased because training data often reflects stereotypes, excludes diverse voices, or favours English and certain regions. Modern AI models work like “black boxes,” making it hard to explain how outputs are produced, which affects trust and accountability. Training on internet data raises copyright concerns, and strict Australian laws mean no AI tools have been trained locally.

Visit the Use section to learn how copyright effects you.

How does Gen-AI work

Despite producing text that sounds human, these tools do not understand meaning. They rely entirely on statistical patterns, which is why their outputs must be checked carefully. Sometimes they generate responses that appear correct but are factually wrong. Think of Gen-AI as a helpful assistant—useful, but requiring review, feedback, and refinement.

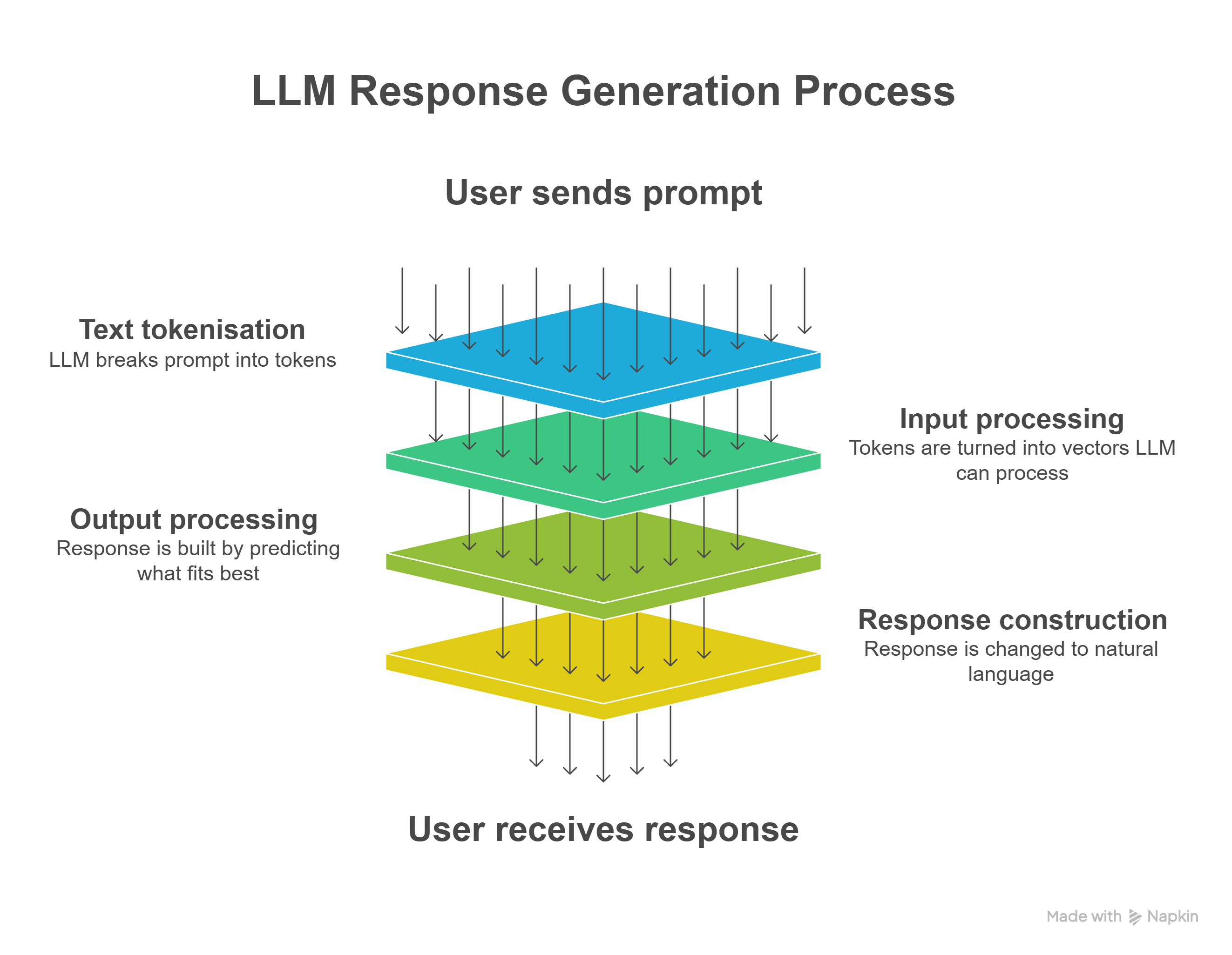

Let’s take a look at the steps that occur when a Gen-AI tool generates written content. You’ll notice nowhere in the process does critical thinking occur - that’s your job.

-

You send a message to the model behind your Gen-AI tool of choice, often Large Language Models (LLMs) like those from OpenAI (ChatGPT), Anthropic (Claude) or Google (Gemini). This message is called a prompt.

-

The LLM breaks your message into small parts called tokens. Tokens can be words, parts of words, or punctuation marks. These tokens are converted to sets of numbers called vectors.

-

The LLM uses the vectors to track how words and phrases are connected. It does this by using maths based on patterns identified from its training data. It may also use earlier messages in the conversation to help.

-

The LLM builds its response one word at a time. At each step, it predicts the word that is most likely to come next based on statistical patterns. The model looks at all the possible words it could choose, calculates which one is most likely to fit, and then adds it to the response. It keeps doing this until the response is complete.

-

The response is changed from tokens back to natural language and returned to you when it is complete.

LLMs operate within a limited context window—typically thousands of tokens. This means they can “remember” recent text in a conversation but not everything they’ve ever processed.

Gen-AI tools generate text based on probability, like advanced predictive text systems. They don’t think or reason—they calculate the most likely sequence of words using patterns learned from huge amounts of data. Each word choice comes from a probability distribution built on billions of examples.

The model doesn’t pick the next word at random; it evaluates context and relationships between tokens using a mechanism called attention. Transformers use this attention process to decide which parts of your prompt are most relevant when predicting the next word, as shown through the connections illustrated in the examples below. Transformers analyse all words simultaneously, calculating attention weights that show the importance of relationships between words.

Transformer Self-Attention

How Transformers Weight Word Relationships

Click on any word to see how the Transformer weighs its relationship with other words. These weights (in percent - %) show how much attention the ‘selected’ word pays to each word in the sentence.

Why This Matters

In the example above, when analysing the word “it”, the Transformer assigns a high attention weight to “animal” (despite the distance between them) and lower weights to other words. This allows the model to understand that “it” refers to “animal” rather than “street.” The model learns these weights during training, enabling it to capture complex linguistic relationships automatically.

Please note: These examples are provided for learning purposes only. The percentages shown do not reflect the exact weighting that would occur in practice.